Imagine how thanks (mostly) to science and technology the developed world has advanced so much that by now we can (over)feed the entire population with just one percent of our economic output(a), yet millions of people on this planet are still starving to death. Or think about how we can cure countless diseases that would have killed us before the advent of modern medicine for just a few euros or dollars, yet millions of children die(1) precisely because they lack access to even the most basic treatments?

While this project, and my main focus, is actually about innovation and its role in solving the world’s remaining problems, I think that this process should start with identifying what the biggest problems are and to set priorities accordingly. In my mind, our number-one priority, and by ‘us’ I mean the people of the developed nations, should be to end extreme poverty, i.e. humans starving or dying of preventable diseases(b).

There are two reasons why I argue that the most extreme forms of poverty should be our utmost priority. The first reason is that people who do not even have enough to eat and no access to basic medicine like painkillers must be in the worst life situations. Of course, there are countless problems we need to solve, like caring for elderly and fighting homelessness. And surely, there is no argument that cancer patients or victims of abuse or rape also suffer a great deal. However, for the poorest of the poor, all these problems (e.g. cancer, abuse, old age) are, of course, just added to their list of problems and further exacerbate their suffering.

While I do not attempt to exactly rank different forms of suffering (I recommend Sam Harris’ “The Moral Landscape” for a scientific approach to ethics) I think the overall life situations – the baseline, in a sense – of these millions of people are the absolute worst in the world and they are, collectively, suffering the most.

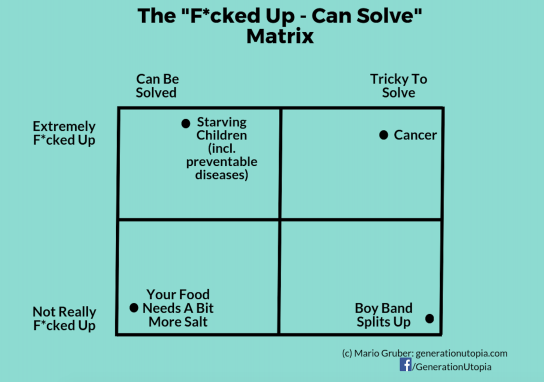

The second reason I think abject poverty should be our top priority is that with new technology and our global reach it is easier and cheaper than ever to vaccinate or feed a child, namely for just a few dollars. While fighting diseases like cancer are extremely important, this is a problem with a viable solution right now. This than raises the question why we don’t put more resources into addressing and ending extreme poverty immediately.

I tried to summarize the arguments above with this little graphic below.

I often hear people say that they believe it is simply too difficult and hopeless to help people in extreme poverty. However, we, the ‘top one billion’, absolutely have the power to help the ‘bottom one billion’. Just look at the work of the UN or Gates Foundation (referenced below), yet we are only dedicating a fraction of a percent, 0.32%(2) that is, of our economic output on development aid. In this regard, private citizens are more generous than governments, which is already a good sign. Disturbingly, of the $1,500 donated to charities per American, the biggest portion goes to religious organizations, e.g. building mega-churches or Scientology, instead of directly helping people. Conversely, three quarters of Europeans donate mostly to poverty relief initiatives directly. Unfortunately, they donate much less than Americans, at only €200 or less(3). To me, a member of the ‘top one billion’, we do not make a very strong impression that we even feel responsible or obliged to help. And many would argue we are not responsible.

In fact, whenever I discuss this topic with friends, I usually hear that they think their donations won’t make a difference anyway, that the West shouldn’t intervene in the business of other countries and that it merely makes matters worse, and so on. These are very dangerous myths that have been repeatedly addressed and are simply untrue – I recommend reading several of the annual Gates letters.

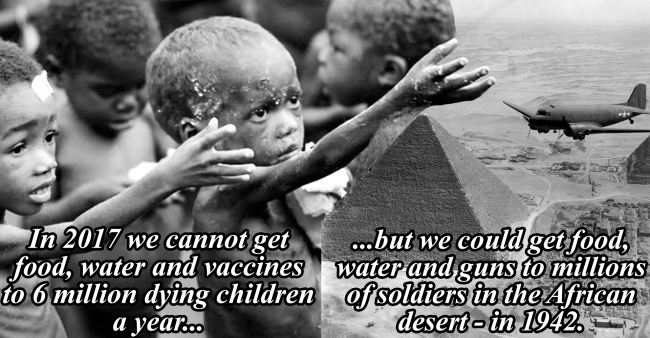

I believe that if these six million children were soldiers, there would be no issues supplying them with basic necessities, no matter where in the world they were. Just think about how even in the second World War, 75 years ago, we managed to supply millions of soldiers in North Africa, in deserts, created infrastructure where there was none and made the impossible possible. And we didn’t just supply them with food, water and medicine, but tanks and weapons and millions of rounds of ammunition. Of course, we can argue about whether some forms of foreign aid are perhaps not useful, that it’s too complex to go into all these regions and to deal with local politics. Certainly, in war-ridden regions, like Syria over the past few years, it is extremely difficult to help the local population. But that’s beside the point – the point I am making is that there is an apparent lack of political, but even more importantly, societal will. That includes, most likely, you.

Granted, to talk about poverty and hunger are not topics most of us like to talk or think about, in fact they’re arguably a conversational taboo, so I suspect we mostly rather just avoid the topic altogether. To me it seems that we would rather ignore the issue, look away, tell ourselves there’s nothing we can do to absolve ourselves from our responsibility or obligation to help. In fact, to me it seems strange to not think and talk about this at all.

Take a second to reflect on the fact how the vast majority of us in the developed world have come a long way from being never more than a few meals or an injury away from death to being able to go to the supermarket or open the fridge and eat. Or how we’ve gone from shivering in the cold in our caves afraid of the dark to being able to flip a switch and turn the heater and the lights on. Arguably a hundred times richer than we were ten thousand years ago, we still don’t want to share more than a single percent of our income with those living in conditions similar to how life was like ten thousand years ago.

So why don’t we do more? Why don’t you do more? And by doing more I don’t just mean giving more money, but also in the form of any kind of political action.

Our societies and democracies are based on social systems that ensure that the sick, the old, and the less fortunate receive medical and financial help. These values first evolved when we were still primitive humans, starting to settle in communities; and they are a part of human nature and what has made us so successful as a species. To imagine and understand another person’s suffering, and not just our own, is part of what makes us sapient, intelligent Homo sapiens. Yet, when people are far away in different countries or cultures, our brains seem to fail to make the same connections.

I think that’s a shame, in fact, even a bit of an embarrassment to many of us in the developed world. In my mind it smacks of ignorance and a disturbing form of cognitive dissonance in that we seem to care only about what we can see or is shown to us in the media in easier-to-digest sound bites. I wonder if future generations will ask us how we could live with such drastic inequality especially when we had the means to help more, but were instead focused so much on our own ‘1st-world problems’.

Of course, people in developed nations are not evil or indifferent to other people’s suffering; and many of us certainly also have serious problems. I believe the problem is that most people are not educated on the topic or are ill-informed. For example, in their 2017 annual letter, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation shows that only 1% of people know that over the past 25 years poverty decreased by half and that, in fact, 70% of people believed that poverty increased by more than 25%(4). Furthermore, it is shown that, yes, extreme poverty can be tackled – with some great successes – and that contributions by the West are strongly related to positive developments:

- Since 1990, the foundation estimates that 122 million children’s lives have been saved – 122 million!

- Another mind boggling fact: For every dollar spent on vaccines, 44 dollars are saved. This is probably my favourite multiplier effect in the entire world (sorry robots that are several times more productive than humans at a much lower cost!).

The take-away lesson here is that there have been people who have donated large amounts of money and others who volunteer to go abroad and together, they make a gigantic difference.

Unless we have serious personal issues, we should, being many times richer and better off than those stuck in extreme poverty, reflect and educate ourselves more to truly understand the significance of this issue and most importantly, to also donate and act more. As Elon Musk once put it, we should spend more on space travel than on lipstick. Similarly, I would argue we – and that means every single one of us – should spend more on saving starving, virus-infected children than we do on our phones.

At the same time I do think that it would be extremely difficult to convince people to donate more money or time to poverty reduction causes – countless brilliant campaigns and hard-working volunteers have been trying that for much longer than me. I’m also not an expert in poverty reduction. However, in the spirit of this project, let’s look at this problem from the perspective of innovation. If we create a more efficient, prosperous economy, I think it would be easier to part with additional income rather than to give away what you have and are used to.

So this could be the deal:

- We agree that in 2017 no child should starve to death or die of diarrhea and that we should spend more resources (more than just 1% of GDP) to solve this problem.

- Look at how to increase our own economic growth – through the lens of innovation, which is what this entire project is about.

- Finally, we agree to give away half (to be perfectly fair to both sides) of any additional (out of nothing) economic growth to the least fortunate of the world. Let’s say 2% is the baseline(e). This way, we won’t lose anything and wouldn’t have to give anything away except what we don’t yet have.

You might wonder how we could simply grow the economy faster and that is a question for hundreds of articles to come on this page, but I firmly believe we can. There is more potential for innovation, economic growth, socio-political change and problem-solving capabilities than ever before.

And if you are not convinced that donations can actually help, leave the headache to the experts that have, year after year, shown that extreme poverty can be tackled surprisingly successfully.

To summarize, the point of this article is to merely raise the question why we in the developed world are doing so relatively little about extreme poverty although it is arguably the biggest problem, and thus arguably also a great responsibility, of our modern world.

References:

1) http://www.who.int/gho/child_health/mortality/mortality_under_five_text/en/

2) http://www.oecd.org/dac/development-aid-rises-again-in-2016-but-flows-to-poorest-countries-dip.htm

3) http://www.gfk-verein.org/en/press/germans-donate-less-money-average-other-europeans

4) https://www.gatesnotes.com/2017-Annual-Letter?WT.mc_id=02_14_2017_02_AL2017_TLK-TLK_&WT.tsrc=TLKTLK

Footnotes:

a) Agriculture usually accounts to about 1% or less of developed countries.

b) This article addresses people of the developed world.

c) I know it’s not quite that easy for some and that many in the developed world also struggle to feed their families, but virtually everybody reading this will live comparatively more comfortable lives.

d) If you are in a difficult situation, financially or health-wise, I do not mean to offend. I simply intend to inspire some self-reflection in as many readers as possible.

e) Of course during recessions this would no longer apply and also, right now most Western economies are growing even faster than 2%. The details can be worked out, but the basic idea makes sense.